In July, Mike Turney was cleared after being charged with the murder of his stepdaughter, Alissa — 22 years after the high school junior vanished. But his son has no doubt the teen, whose body has never been found, was his father’s victim.

“There’s no justice in the system for her,” James Turney, 49, told NBC News. “It failed her 100 %.”

Now, James is speaking out about the often misunderstood type of abuse, known as coercive control, that he said Alissa suffered for years — allegations that include intimidation, surveillance and psychological abuse. And he’s calling out Arizona prosecutors for downplaying what one expert called a “textbook” example of coercive control.

Although he has no expectation of justice for Alissa, James said he hopes she serves as a grim but instructive reminder to others facing what Evan Stark, the social worker who first defined coercive control, has described as a hostage situation aimed at erasing a person’s liberty and a predictor of fatal violence.

For more on the case, watch “The Day Alissa Disappeared“ on Dateline at 9 ET/8 CT tonight.

James pointed to countries like Scotland, where coercive control has been codified in criminal law and the country has provided judicial training and support for victims, as a model of reform for the United States.

Lawmakers in a handful of states, including California and Connecticut, have enacted laws in recent years allowing victims to cite the abuse in civil matters, including petitions for protection orders. In Hawaii, the abuse is a misdemeanor.

Though Mike, 75, was charged with second-degree murder after Alissa’s disappearance, he was acquitted during a six-day trial in a Phoenix courtroom. Before the case went to the jury, Mike’s defense attorneys argued there wasn’t substantial evidence to support the charge — a claim the judge agreed with.

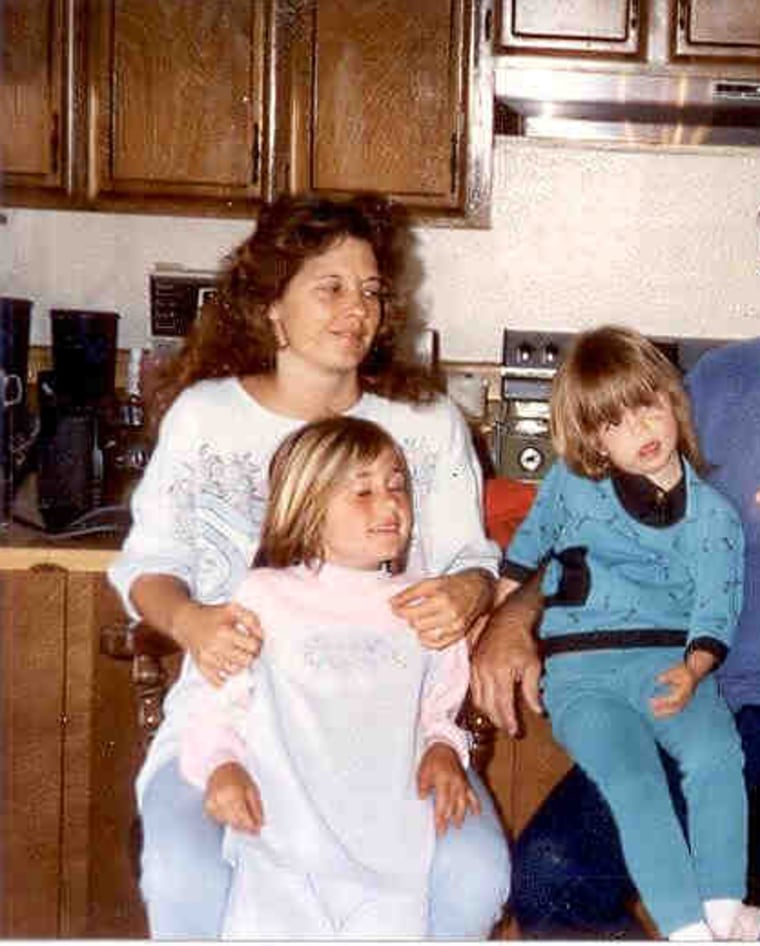

Mike has not been charged with any crimes in connection to the abuse and coercive control allegations. In an interview with NBC’s “Dateline,” the former Maricopa County sheriff’s deputy denied abusing his stepdaughter, whom he adopted shortly after he and his wife got together in 1986, though he acknowledged being a controlling parent, saying it was necessary because Alissa needed “constant supervision.”

Mike told “Dateline” he was trying to protect a teenager who he said was “very naive” and “easily influenced.” (Mike’s wife — Alissa’s mother — died when she was in second grade.)

But to James, the second oldest in the blended family of six children, his father is a “master manipulator” who routinely called Alissa “stupid” and “not that intelligent.”

Mike also said things that seemed far more cruel. He had recording systems inside his suburban Phoenix home that captured phone calls as well as video — a camera was tucked inside an air conditioning vent in the living room — and audio tapes recovered by authorities captured him making disparaging comments about Alissa and using expletives to describe her.

From the camera inside the vent, Mike saw Alissa kissing someone who wasn’t her boyfriend — then revealed to the boyfriend that his stepdaughter was “cheating” on him, William Andersen, the Phoenix police detective who led the investigation into Alissa’s disappearance, told “Dateline.”

Mike also regularly appeared at Alissa’s job — she worked at a Jack in the Box — and filmed her from his car, Andersen said.

“Mr. Turney has stated that he would routinely show up an hour or two early to ensure she did not leave the premises with anybody else,” Andersen said. “It’s very much over the top.”

Mike said it was a “lie” that he disclosed his stepdaughter’s cheating. He said he initially filmed Alissa at her job because she asked him to — he said she wanted to be recorded at her first job — and he later did so because he believed she was giving her phone number to men at the drive-thru.

Mike said he placed the camera inside the air-conditioning vent because someone had tried to break in when his children were home alone. He made the disparaging comments, he added, because he discovered Alissa was doing drugs, having sex and lying to him.

A co-worker of Alissa’s, Cris Ridenour, painted a different picture of his friend. He said it was possible Alissa was giving out her number to random guys, though he never saw it, nor did he know her to sleep around or do drugs.

“She seemed bothered by her home life,” he told “Dateline.” “But when she was at work, it looked like she was happier, you know? Like she was away from whatever it was.”

Disturbing allegations

Other allegations of abuse came from several people who knew Alissa. Three different sources — including Alissa’s then-boyfriend — told investigators that she described Mike driving her to the desert and touching her inappropriately, Andersen said.

In an interview with police, another friend said that Alissa described waking up to her father gagging her with a sock — and telling her to remain quiet about the event because no one would believe her, according to a recording of the interview obtained by “Dateline.”

Mike has previously denied that allegation.

Alissa’s third-grade teacher told authorities that the teen once confided in her that she was having sex with her father. The teacher did not report the allegation to authorities because she said that Alissa immediately denied it. But the teacher confronted Mike, Andersen said, and he denied it, saying Alissa believed “sex is when people kiss each other goodnight.”

A year before Alissa disappeared, Mike called child protective services with a warning: His stepdaughter might falsely claim that he was molesting her, Andersen said. He also made her sign a notarized contract — “my statement about things in my life at home” — saying that he hadn’t abused her, Andersen said. (He made her sign other contracts that focused on drug use and behavioral issues, the detective said.)

“It’s a form of humiliation,” Andersen said of the notarized document. “It’s intimidation. With this document, Mike can turn around and say, ‘You can never accuse me of any of these things because you’ve signed your life away.’”

Mike described the contracts as a way to give Alissa structure — “If you told Alissa something within an hour or so, she didn’t remember it,” he said — and the notarized document as a means of protecting himself from what he described as Alissa’s false allegations. He said Alissa had been “threatening” him with child protective services as part of an effort to “emancipate” herself from home.

Asked if he sexually abused Alissa, Mike said: “I never did, and I would never do anything like that.”

It took years for prosecutors to file criminal charges in Alissa’s disappearance — a result of authorities initially believing she was a runaway and the voluminous audio and video evidence investigators had to sift through.

But after Mike was indicted for second-degree murder in 2020, the sex abuse claims were at the heart of the prosecution’s theory of the case: Mike believed she would reveal the abuse, prosecutors at the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office alleged.

But the judge ruled those claims were hearsay and barred prosecutors from discussing them.

Mike said the motive was “fabricated” and based on “lies told by people that say that Alissa said this.” His lawyers dismissed the case as thin on real evidence.

“For me, it was immediately, ‘Wow, there’s very little physical evidence, obviously, in this case, or none,'” one of the lawyers, Jamie Jackson, told “Dateline.” “And it seemed that this all became kind of a character assassination.”

‘Taken away somebody’s liberty’

To Stark, who authored the 2007 book “Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life,” Alissa’s case appeared to be an “open and shut” example of the abuse.

Stark, who wasn’t familiar with the case but reviewed the allegations for NBC News, pointed to the surveillance, the contracts and other aspects of Mike’s behavior and said: “Once you put all these elements together, even if you don’t have physical violence, you have the elements of a coercive control crime because you’ve taken away somebody’s liberty.”

More ‘Dateline’ cases

Coercive control that ends with a homicide, Stark added, means the pattern of abuse failed.

Coercive control is not a criminal offense in Arizona. Still, James believed it defined his father’s relationship with his stepsister and he feared the jury in his father’s case wouldn’t connect the dots between what may appear to be a series of unusual behaviors and what he described as brutal, systematic abuse, including filming her at work and routinely saying disparaging things about her.

During the trial, the Maricopa County prosecutor who delivered the opening statement, Vince Imbordino, said that Mike “attempted to basically control every part” of Alissa’s life.

But to James, who attended the proceedings, prosecutors did little to link his father’s allegedly abusive behaviors. They didn’t present the surveillance as part of a pattern, for instance, but as a strange habit, he said. He said he begged prosecutors to call expert witnesses who could help the jury make sense of the alleged abuse and explain the corrosive dynamics of coercive control.

“Why is no one putting this all together?” he recalled telling prosecutors at the time. “Why are we not showing that this is a pattern of events? Stop saying individual, isolated things — you need to connect them.”

“You need to show that this was going on throughout her life,” James added. “This wasn’t a one-time bad parenting decision.”

Pushing prosecutors to dig deeper

With the help of a forensic psychologist relative, James even lined up possible experts and emailed prosecutors potential lines of questioning they could pursue. But the prosecutors declined, James recalled, and said it wasn’t necessary and wouldn’t be effective.

In an interview, Imbordino said that he believed James wanted testimony related to coercive control to help establish a motive.

“That wasn’t our problem,” Imbordino said. “We had motive.”

It’s unclear what role expert testimony would have played in the case. After prosecutors rested — and before either side presented their closing arguments — Mike’s lawyers argued there was a lack of physical evidence and asked the judge to throw out the charge.

The judge agreed. Prosecutors hadn’t put forward “substantial evidence” to warrant a conviction, the judge ruled. Mike Turney was acquitted of second-degree murder.

Prosecutors disagreed with the decision but accepted it, Imbordino said. The statute of limitations on other potential charges, such as stalking or entrapment, have expired, he added.

To Stark, the prosecution’s decision not to take up James’ request was a mistake — one that could have not only raised awareness about coercive control through a high-profile criminal trial, but also potentially shifted the case’s outcome.

An expert, Stark said, could have reframed what seemed like relatively trivial behaviors — such as the surveillance — as contributing elements to a homicide. Those elements could have been presented as part of an “ongoing course of malevolent conduct designed to dominate and deprive that girl of her liberties and her dignity, and ultimately culminating in her death,” he said.

Though Mike was acquitted, James still believes that his father killed his stepsister, though he’s unsure what would have prompted him to do so. But a request she made in the weeks before her disappearance continues to linger: She wanted to leave her father’s home, James recalled her saying, and move in with him.

“She couldn’t take living with my father anymore,” he said. “She was afraid of him.”

Mike told “Dateline” that he did not believe Alissa feared him. And he said he’s unsure what happened to her.

“I have no idea where Alissa is, alive or dead,” he said.